Understanding Actors in the New Concurrency Model in Swift

Published on

This article is part of my Modern Concurrency in Swift Article Series.

Table of Contents

- Modern Concurrency in Swift: Introduction

- Understanding async/await in Swift

- Converting closure-based code into async/await in Swift

- Structured Concurrency in Swift: Using async let

- Structured Concurrency With Task Groups in Swift

- Introduction to Unstructured Concurrency in Swift

- Unstructured Concurrency With Detached Tasks in Swift

- Understanding Actors in the New Concurrency Model in Swift

- @MainActor and Global Actors in Swift

- Sharing Data Across Tasks with the @TaskLocal property wrapper in the new Swift Concurrency Model

- Using AsyncSequence in Swift

- Modern Swift Concurrency Summary, Cheatsheet, and Thanks

When we are working with concurrency, the most common problem developers face are data races. Whether it is a task updating a value at the same time another task is reading it or two tasks writing a value so that it it has an invalid value, data races are probably the main pain point of concurrency. Data races are very easy create, and hard to debug. There are entire books dedicated to the problem of data races and established patterns to avoid them.

Data races happen when there’s shared mutable state. If you are only working with let variables that are never mutated, you are unlikely to encounter them. Unfortunately, even the most trivial of programs does have mutable state at some point, so racking your brain to make everything immutable is not going to yield results. In general, preferring to use let as much as possible and using value semantics (like structs) is going to help a lot when dealing with data races.

Shared mutable state requires synchronization. In the most basic - and hardest - form, you can make use of locks (a concept that guarantees mutable state will only be modified by one process at a time) and other primitives. In the past few years, many Apple Platform developers have used serial dispatch queues, which are higher level concepts for dealing with concurrency. Going this route requires you to write all that code.

Luckily, with Swift 5.5 and the new concurrency APIs introduced at WWDC2021, Swift now has a much easier way to deal with mutable state, ensuring that only one process at a time modifies a value. Of course, this has the same implications as the other new concurrency APIs we have seen so far in this series. It iss easy to use, but may be limiting if you need more control. The good news is that the actors API is going to be enough for the vast majority of developers.

Introducing actors

Actors provide synchronization for mutable state automatically, and they isolate their state from the rest of the program. This means that nobody can modify the shared state unless they go through the actor itself. Because the actor is isolated and you need to talk to it to modify values, the actor ensures that access to its state is mutually exclusive. Only one process will be able to modify its state at a time. Behind the scenes, actors will take care of the manual synchronization for you, and it will “queue up” processes as they attempt to modify it so they only do so one at a time.

Implementation details

actors in Swift are implemented as actor types. Similar to how you define classes, enums, and structs, you declare an actor by using the actor keyword. Actors are reference types, meaning that their behaviors are more similar to classes than structs. Which makes complete sense if you think about it, as actors are all about hiding shared mutable state that other types may need to access. The main differences between actors and classes is that actors implement all the synchronization mechanisms behind the scenes, their data is isolated from the rest of the program, and actors cannot inherit or be inherited from, although they can conform to protocols and be extended.

Thanks to the fact that actors are integrated deeply into the Swift compiler, Swift will do a lot to protect you against code that may run haywire due to its concurrency needs.

Consider the following example:

class Counter {

var count = 0

func increment() -> Int {

count += 1

return count

}

}

class ViewController: UIViewController {

var tasks = [Task<Void, Never>]()

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

let counter = Counter()

tasks += [

Task.detached {

print(counter.increment())

}

]

tasks += [

Task.detached {

print(counter.increment())

}

]

}

}

(Apple uses a similar example in the Protect mutable state with Swift actors WWDC2021 session)

Also, I originally intended to provide a sample Playground with these examples, but I couldn’t get it to work as of Xcode 13 Beta 4, so I will provide a standard iOS project instead at the end of this article)

In this example, you are attempting to increment the counter variable inside detached tasks. There is no locking mechanism or any synchronization that ensures that the code will work as you expect it to work. The system could increment to 0 both times, and the values that get printed can be drastically different on each turn.

We can fix it and ensure that the output is always “1, 2” by making Counter an actor instead of a class.

actor Counter {

var count = 0

func increment() -> Int {

count += 1

return count

}

}

Simply making this change will not be enough. Trying to compile and run it will give you this error in both places where we try to print:

Expression is 'async' but is not marked with 'await'

This is beautiful, and it really shows you how deeply concurrency is implemented at the compiler level to save you from writing buggy concurrent code. It can save you from having to spend hours, days, months, or even years, learning to write concurrent code safely yourself. I absolutely love the compiler integration, because it also shows you that all the concepts we have explored throughout this series converge. The compiler is helping us make sense of everything we learned so far.

To fix that error, simply add await when you call increment().

print(await counter.increment())

All of an actor’s public interface are automatic made async for its consumers. This allows us to safely interact with actors, because using the await keyword will suspend execution until the code is notified that it can go into the actor next and do its job.

(This is a good point to stop and think if you actually understand async/await, which are the most basic building blocks for the new concurrency system in Swift. If you think you need a refresher, you can read the Understanding async/await in Swift article of this series.)

Do note that this has some implications when attempting to access the properties (in this case, count) directly. First, you can do read-only access, but it has to be done through asynchronous contexts. This therefore, will not work:

print(counter.count)

It will make the compiler yell at you with:

Actor-isolated property 'count' can only be referenced from inside the actor

This is because, just like methods, properties expose their getters as async.

async {

let count = await counter.count

print("count is \(count)")

}

Finally, remember when we said nobody can modify the shared state in an actor without going through the actor itself? This means that the actor has to expose methods that would modify its values. You cannot modify properties of an actor directly.

counter.count = 3

Actor-isolated property 'count' can only be mutated from inside the actor

Inside the actor

The actor will expose asynchronous code to external callers, helpfully marking everything relevant as async. But within the actor itself, all calls are synchronous. This will help you write more natural code within the actor as you won’t have to worry about weird execution orders.

You can observe this yourself, add the following method to Counter.

func reset() {

while count > 0 {

count -= 1

}

print("Done resetting")

}

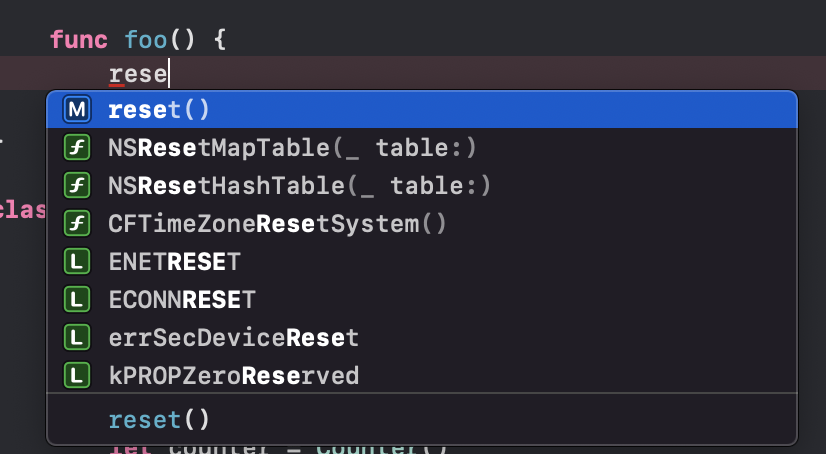

Then, create a new function, foo, and typing reset within it. You will see that the autocomplete suggestions will suggest you autofill with reset().

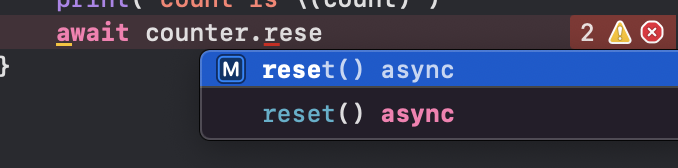

Whereas, if you call reset externally, you will see that the reset() method has async on its signature.

.

.

You can see that anything called within the actor is synchronous (as you can tell due to the lack of the async keyword), but calling the very same methods externally are async. Synchronous code on the actor always runs to completion without being interrupted. You will notice you cannot await on the actor’s properties or methods, although nothing prevents the actor from calling async methods from other actors or other places.

Actor reentrancy

While actors isolate their own state from others, they rarely work alone. They are likely to interact with other actors or with the rest of your codebase in general.

This can cause unexpected behavior. Consider the following example:

enum ImageDownloadError: Error {

case badImage

}

func downloadImage(url: URL) async throws -> UIImage {

let imageRequest = URLRequest(url: url)

let (data, imageResponse) = try await URLSession.shared.data(for: imageRequest)

guard let image = UIImage(data: data), (imageResponse as? HTTPURLResponse)?.statusCode == 200 else {

throw ImageDownloadError.badImage

}

return image

}

actor ImageDownloader {

private var cache: [URL: UIImage] = [:]

func image(from url: URL) async throws -> UIImage {

if let image = cache[url] {

return image

}

let image = try await downloadImage(url: url)

cache[url] = image

return image

}

private func downloadImage(url: URL) async throws -> UIImage {

let imageRequest = URLRequest(url: url)

let (data, imageResponse) = try await URLSession.shared.data(for: imageRequest)

guard let image = UIImage(data: data), (imageResponse as? HTTPURLResponse)?.statusCode == 200 else {

throw ImageDownloadError.badImage

}

return image

}

}

(This code is similar to Apple’s ImageDownloader code from their Protect mutable state with Swift actors WWDC2021 session, but I have created a sample you can run.

We have an image downloader that caches images so as to not download them again. The if let will check if an image is cached and return it if possible. Otherwise the code will download an image, cache it after the download, and return the newly downloaded image. But what happens if we enter here twice?

Consider the following code that uses the ImageDownloader actor from above:

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

Task.detached {

await self.downloadImages()

}

}

//...

func downloadImages() async {

let downloader = ImageDownloader()

let imageURL = URL(string: "https://www.andyibanez.com/fairesepages.github.io/tutorials/async-await/part3/3.png")!

async let downloadedImage = downloader.image(from: imageURL)

async let sameDownloadedImage = downloader.image(from: imageURL)

var images = [UIImage?]()

images += [try? await downloadedImage]

images += [try? await sameDownloadedImage]

}

Important Note: As of Xcode 13 Beta 4 (and all the way down to Beta 3), there is a bug that causes your code to deadlock when entering an actor twice from the same Task via async let. Apple is aware of this issue, and it will hopefully be fixed in a later beta. Until this bug is fixed, the workaround is to use Task.detached instead of just Task when using more than one async let binding at the same time. By the time a later Beta comes out, the GM, or the final release comes out, the bug may be fixed. Please keep that in mind as ultimately, normal Tasks and Task.detached calls have different uses.

We are entering the actor via two different async let calls. The first call (downloadedImage) will enter the actor and it will execute until it finds the await call on downloadImages. It will suspend, and the second call, sameDownloadedImage will begin executing. Note that downloadedImage reached the await, and since it suspended, it hasn’t had any time to download the image yet. And because the image is not in the cache, sameDownloadedImage will also download the image instead of retrieving it from memory. If you are really unlucky, the server may have updated the image behind the same URL, so downloadedImage and sameDownloadedImage may download different things!

The problem is we are assuming the program state after the await call. It’s like we are telling the program “Hey, you will download the image, cache it, and anyone else who access it, will grab the cached version”. But in reality, it’s impossible to make this guarantee with this code, because there may be different calls attempting to access the actor at the same time, and thus we have this bug that hits the network twice for the same image.

To work around this, we can make our actor keep the state of each download, and access that state first-thing before our actor tries to download an image:

actor ImageDownloader {

private enum ImageStatus {

case downloading(_ task: Task<UIImage, Error>)

case downloaded(_ image: UIImage)

}

private var cache: [URL: ImageStatus] = [:]

func image(from url: URL) async throws -> UIImage {

if let imageStatus = cache[url] {

switch imageStatus {

case .downloading(let task):

return try await task.value

case .downloaded(let image):

return image

}

}

let task = Task {

try await downloadImage(url: url)

}

cache[url] = .downloading(task)

do {

let image = try await task.value

cache[url] = .downloaded(image)

return image

} catch {

// If an error occurs, we will evict the URL from the cache

// and rethrow the original error.

cache.removeValue(forKey: url)

throw error

}

}

private func downloadImage(url: URL) async throws -> UIImage {

let imageRequest = URLRequest(url: url)

let (data, imageResponse) = try await URLSession.shared.data(for: imageRequest)

guard let image = UIImage(data: data), (imageResponse as? HTTPURLResponse)?.statusCode == 200 else {

throw ImageDownloadError.badImage

}

return image

}

}

This code is similar to the code provided by Apple in the Protect mutable state with Swift actors WWDC2021 session.

This looks like a mouthful, but it’s very straightforward (and straightforwardness is the power of the new concurrency APIs!). We start by declaring an enum that will hold the state for the current URL. When a URL is downloaded for the first time, we will add this URL to the cache with a .downloading status. If any other call is made to the actor with the same URL at the same time, it will see the image is in the cache, so rather than downloading the image again, it will directly await on it. Calls made in a farther future will likely see an already downloaded image, so they will return immediately. When the image finishes downloading for the first (and) last time. the image is cached with a .downloaded status.

Actor reentrancy prevents deadlocks and guarantees forward progress, but it is necessary that you check your assumptions so as to prevent any other bugs that are not necessarily related to concurrency, such as downloading the same image more than once. Here’s a few points to make sure you play with the actor reentrancy concept well:

- Make mutations in synchronous code. You can see that we mutate our cache in the same task, and we are not attempting to update it anywhere else.

- Know that state can change at any point after you hit an

await. You may need to manually check for some state to determine how it has changed so you can respond to it if necessary.

Actor isolation

Actors are all about isolation. Their main purpose is to isolate their state from others, so they can manage access to their own properties, ensuring that multiple writes are performed at the same time, which could leave your program in an unexpected state.

Immutable properties can be accessed at any time.

actor DollMaker {

let id: Int

var dolls: [Doll] = []

init(id: Int) {

self.id = id

}

}

extension DollMaker: Equatable {

static func ==(_ lhs: DollMaker, rhs: DollMaker) -> Bool {

lhs.id == rhs.id

}

}

In the code above, the == operator compares two types, and it is a static method. static means that this method is “outside” of the actor (there’s no self instance). Combine that with the fact we only access immutable state within the method, and the compiler knows this is a safe thing to do.

extension DollMaker: Hashable {

func hash(into hasher: inout Hasher) {

hasher.combine(id)

}

}

On the other hand, this is getting into murky waters. While we also only reference the id field, this method is an instance method. It is supposed to be async to be isolated. Luckily, in this case, we can explicitly mark the method as nonisolated to let the compiler know this is not isolated. The compiler will treat this method as being “outside” the actor, and move on, as long as you only access immutable properties inside of it. If the hasher was using the dolls property instead of id, this wouldn’t work as dolls is mutable.

The Sendable Type

The concurrency model also introduces Sendable types. Sendable types are those that can be shared concurrently safely. The following are some examples of types that are Sendable:

- Value types (such as structs)

- Actor types

Classes can be Sendable but only if they are immutable or if they provide their own synchronization within themselves. Sendable classes are exceptional.

It is recommended that your concurrent code communicates using Sendable types. At some point, Swift will be able to check, at compile time, if you are sharing non Sendable types across functions, but this doesn’t appear to be the case as of Xcode 13, Beta 4.

The Sendable Protocol

You probably guessed it, but the way we make types Sendable is by making our types conform to the Sendable protocol. Just by specifying the conformance, the Swift compiler will do a lot of work for us.

Consider the following example:

struct Videogame: Sendable {

var title: String

}

struct VideogameMaker: Sendable {

var name: String

var games: [Videogame]

}

This will compile without an issue, because VideogameMaker is sendable, and so is Videogame.

For structs, you can avoid conforming to Sendable, and it will still work:

struct Videogame {

var title: String

}

struct VideogameMaker: Sendable {

var name: String

var games: [Videogame]

}

But this is not the case with classes.

class Videogame {

var title: String

init(title: String) {

self.title = title

}

}

struct VideogameMaker: Sendable {

var name: String

var games: [Videogame]

}

You will get an error like this:

Stored property 'games' of 'Sendable'-conforming struct 'VideogameMaker' has non-sendable type '[Videogame]'

Sendable and generics

A Generic type can be Sendable only if its all properties are Sendable.

struct Pair<T, U> {

var first: T

var second: T

}

extension Pair: Sendable where T: Sendable, U: Sendable {}

Sendable functions

For functions that can be passed across actors, they can be made marked as @Sendable.

When it comes to closures, marking them as @Sendable impose some restrictions. They cannot capture mutable variables from their surrounding scope, everything they capture must be Sendable, and finally, they cannot be both asynchronous and actor isolated.

Conclusion

A sample project for the image download can be downloaded from here.

In this article we explored what actors are and how to use them. We learned that an actor isolates its own state and all write access to its properties must be done through the actor itself. By isolating their own state, actors provide concurrency safety.

We also learned about Sendable types and how they are crucial to the new concurrency system in Swift. Sendable types help provide compile-time checks to write concurrent code. As they provide static checking, it’s very hard to write incorrect code that breaks the concurrency model or introduces concurrency bugs.